TL;DR: Dive deeper and learn to group similar company/merchant names. This is helpful when there are many similar strings which is difficult to be corrected manually.

Here’s a common problem that many of us have encountered at least once.

| Row | Merchant Name | Category |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amazon Pay | Payments |

| 1 | 1mg Techn | Healthcare |

| 2 | P Amazon | Payments |

| 3 | 1mg Tech | Healthcare |

| 4 | AmazonPaa | Payments |

Here, row 0, 2, and 4 belong to the same merchant name with slight changes in spelling and formatting. Same is the case with row 1 and 3.

Ideally, there would be an easy way to add a new column like this:

| Row | Merchant Name | Category | Grouped Merchant Names |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Amazon Pay | Payments | Amazon Pay |

| 1 | 1mg Techn | Healthcare | 1mg Tech |

| 2 | P Amazon | Payments | Amazon Pay |

| 3 | 1mg Tech | Healthcare | 1mg Tech |

| 4 | AmazonPaa | Payments | Amazon Pay |

So, how do we tackle this problem to group similar merchant names for a huge dataset in less time and with great accuracy? Let’s find out how.

During my internship @ NiYO, I made the v1 model of merchant name cleaning by solving the problem discussed, and also improved the accuracy by 10% with which the dirty merchant names were cleaned in the v0 model.

Let us take a quick look at the working of the v0 model to have some ground reality about the problem which we are going to solve.

v0

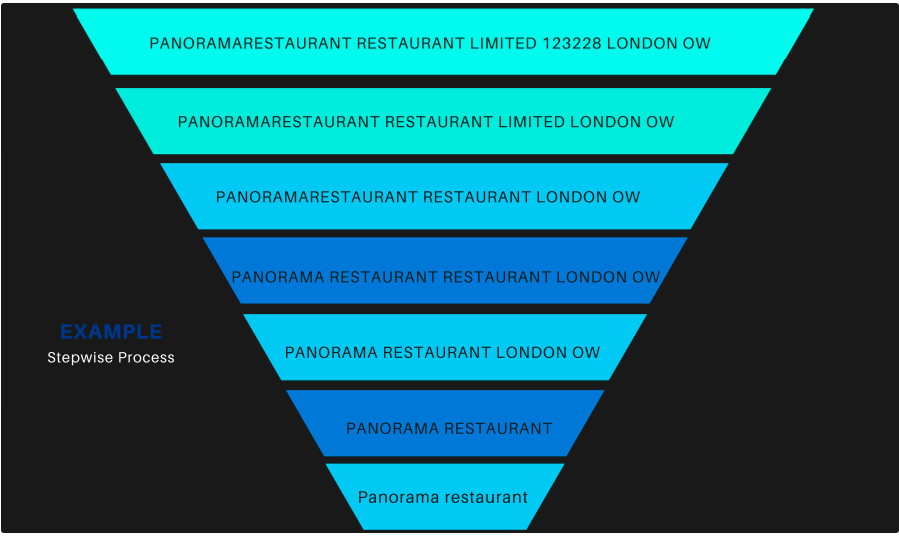

It is a heuristic model which includes the following 7 step procedure:

- Intelligent Number checking and removal

- Unwanted word removal

- Split compound words

- Remove repetitive words

- Country and city removal

- Single/ Double word removal

- Case correction

Refer to the figure below to understand exactly how a dirty merchant name is cleaned following the 7 steps.

Now that we have the gist of the v0 model, let us proceed towards the v1 model which solves the limitation of the v0 model.

v1

It involves a 3-step procedure:

- Building a Document Term Matrix with TF-IDF and N-Grams

- Using cosine similarity to calculate proximity between strings

- Using a hash table to convert our findings to a “grouped” column in our spreadsheet.

For this model, I used dataset consisting of around 60,000 merchant names along with their merchant_id, mcc_code, and merchant_country_code which is generated corresponding to each transaction done under NiYO Card. I cannot share the dataset for undisclosed reasons

Step I: Build a Document Term Matrix with TF-IDF and N-Grams

The biggest challenge here is to compare each row with every other entry in the column which leads to O(n^2) order of complexity for n almost equal to 60,000 which is not feasible.

It would be much faster if we could use matrix multiplication to make simultaneous calculations, which we can do with a Document Term Matrix, TF-IDF, and N-Grams.

Let us define those terms:

Document Term Matrix

A Document Term Matrix is essentially an extension of the Bag of Words (BOW) concept.

BOW involves counting the frequency of words in a string. So, given the sentence: “Rhode Island is neither a road nor is it an island. Discuss.”

We can produce a BOW representation like this:

+---------+-------+

| term | count |

+---------+-------+

| rhode | 1 |

| island | 2 |

| is | 2 |

| neither | 1 |

| a | 1 |

| road | 1 |

| nor | 1 |

| it | 1 |

| an | 1 |

| discuss | 1 |

+---------+-------+

A Document Term Matrix (DTM) extends BOW to multiple strings (or, in the nomenclature, “multiple documents”). Imagine we have the following three strings:

- “Even my brother has needs”

- “My brother needs a lift”

- “Bro, do you even lift?”

The DTM could look like this:

The value of each entry is determined by counting how many times each word appears in each string.

The problem with the above approach is that insignificant words like ‘the’, ‘is’ and ‘if’ tend to appear more frequently than important words, which could skew our analysis.

Thus, instead of counting words, we can assign them a TF-IDF score, which evaluates the importance of each word to the DTM.

TF-IDF

To calculate TF-IDF scores, we multiply the number of times a term appears in a single document (Term Frequency or TF) by the significance of the term to the whole corpus (Inverse Document Frequency or IDF) — the more documents a word appears in, the less valuable that word is thought to be in differentiating documents from one another.

Take a gander here if you are interested in the math behind calculating TF-IDF scores.

The important takeaway is that, for each word in our Document Term Matrix, if we replace the word count with a TF-IDF score, we can weigh words more effectively when checking for string similarity.

N-Grams

Finally, we’ll tackle this problem:

Burger King is two words. BurgerKing should be two words, but a computer will see it as one. Thus, when we calculate our Document Term Matrix, these terms won’t match.

N-grams are a way of breaking strings into smaller chunks where N is the size of the chunk. So, if we set N to 3, we get:

['Bur', 'urg', 'rge', 'ger', 'er ', 'r K', ' Ki', 'Kin', 'ing']

and

['Bur', 'urg', 'rge', 'ger', 'erK', 'rKi', 'Kin', 'ing']

which have significantly more overlap than the original strings.

Thus when we construct our Document Term Matrix, let’s calculate the TF-IDF score for N-Grams instead of words.

Finally, some code: Here’s the code for building a Document Term Matrix with N-Grams as column headers and TF-IDF scores for values:

import re

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

#Import your data to a Pandas.DataFrame

df = pd.read_csv('')

#Grab the column you'd like to group, filter out duplicate values

#and make sure the values are Unicode

vals = df['merchant_name'].unique().astype('U')

#Write a function for cleaning strings and returning an array of ngrams

def ngrams_analyzer(string):

string = re.sub(r'[,-./]', r'', string)

ngrams = zip([string[i:] for i in range(5)])

return [''.join(ngram) for ngram in ngrams]

#Construct your vectorizer for building the TF-IDF matrix

vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer(analyzer=ngrams_analyzer)

#Build the matrix!!!

tfidf_matrix = vectorizer.fit_transform(vals)

Sparse vs Dense matrices and how to crash your computer

The result of the above code, tfidf_matrix, is a Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) matrix.

If you are unfamiliar with sparse matrices, this is a great introduction. For our purposes, know that any matrix of mostly zero values is a sparse matrix. This is distinct from a dense matrix of mostly non-zero values.

There’s no reason to store all those zeros in memory. If we do, there’s a chance we’ll run out of RAM and trigger a MemoryError.

Enter the CSR matrix, which stores only the matrix’s nonzero values and references to their original location.

This is an oversimplification and you can learn the nitty-gritty here. The important takeaway is that the CSR format saves memory while still allowing for fast row access and matrix multiplication.

Step II: Using cosine similarity to calculate the proximity between strings

Cosine similarity is a metric between 0 and 1 used to determine how similar strings are irrespective of their length.

It measures the cosine of the angle between strings in a multidimensional space. The closer that value is to 1 (cosine of 0°), the higher the string similarity.

Here’s a deeper explanation to understand this topic in detail.

Calculating cosine similarity in python.

We could use scikit-learn to calculate cosine similarity. This would return a pairwise matrix with cosine similarity values like:

We would then filter this matrix by a similarity threshold — something like 0.75 or 0.8 — to group strings we believe represent the same entity.

However, if instead, we use this module built by the data scientists at ING Bank, we can filter by our similarity threshold as we build the matrix. The approach is faster than scikit-learn and returns a less memory-intensive CSR matrix for us to work with.

ING wrote a blog post explaining why, if you’re interested.

So, let’s add the following to our script:

#Import IGN's awesome_cossim_topn module

from sparse_dot_topn import awesome_cossim_topn

#The arguments for awesome_cossim_topn are as follows:

#1. Our TF-IDF matrix

#2. Our TF-IDF matrix transposed (allowing us to build a pairwise cosine matrix)

#3. A top_n filter, which allows us to filter the number of matches returned, which isn't useful for our purposes

#4. This is our similarity threshold. Only values over 0.8 will be returned

cosine_matrix = awesome_cossim_topn(

tf_idf_matrix,

tf_idf_matrix.transpose(),

vals.size,

0.8

)

Now we have a CSR matrix representing the cosine similarity between all our strings.

Step III: Build a hash table to convert our findings to a “groups” column in our spreadsheet

We’re now going to build a Python dictionary with a key for each unique string in our merchant_name column.

The fastest way to do this is to convert our CSR matrix to a Coordinate (COO) matrix. A COO matrix is another representation of a sparse matrix.

By example, if we have this sparse matrix:

+------------+

| 0, 0, 0, 4 |

| 0, 1, 0, 0 |

| 0, 0, 0, 0 |

| 3, 0, 0, 7 |

+------------+

And we convert it to a COO matrix, it will become an object with three properties — row, col, data — that containing the following three arrays, respectively:

- [0, 1, 3, 3] The row index for each non-zero value (0-indexed)

- [3, 1, 0, 3] The column index for each non-zero value (0-indexed)

- [4, 1, 3, 7] The non-zero values from our matrix

Thus, we can say that the coordinates for the value 4(stored in matrix.data[0]) are (0,3)(stored in (matrix.row[0],matrix.col[0]).

Let’s build our COO matrix and use it to populate our dictionary:

#Build a coordinate matrix from a cosine matrix

coo_matrix = cosine_matrix.tocoo()

#Instaniate our lookup hash table

group_lookup = {}

def find_group(row, col):

#If either the row or the col string have already been given

#a group, return that group. Otherwise return none

if row in group_lookup:

return group_lookup[row]

elif col in group_lookup:

return group_lookup[col]

else:

return None

def add_vals_to_lookup(group, row, col):

#Once we know the group name, set it as the value

#for both strings in the group_lookup

group_lookup[row] = group

group_lookup[col] = group

def add_pair_to_lookup(row, col):

#in this function we'll add both the row and the col to the lookup

group = find_group(row, col)

if group is not None:

#if we already know the group, make sure both row and col are in lookup

add_vals_to_lookup(group, row, col)

else:

#if we get here, we need to add a new group.

#The name is arbitrary, so just make it the row

add_vals_to_lookup(row, row, col)

#for each row and column in coo_matrix

#if they're not the same string add them to the group lookup

for row, col in zip(coo_matrix.row, coo_matrix.col):

if row != col:

#Note that what is passed to add_pair_to_lookup is the string at each index

#(eg: the names in the legal_name column) not the indices themselves

add_pair_to_lookup(vals[row], vals[col])

Again, take this cosine matrix:

If we’d built it using awesome_cossim_topn with the threshold set to 0.8 and then converted it to a COO matrix, we could represent it like this:

(row, col) | data

------------|------

(0,0) | 1

(0,2) | 0.84

(1,1) | 1

(2,0) | 0.84

(2,2) | 1

vals would equal [‘Walmart’, ‘Target’, ‘Wal-mart stores’].

Thus, inside the loop, our first (row, col) pair to pass the row != col conditional would be (0, 2) which we then pass to add_pair_to_lookup as (vals[0], vals[2]) or (‘Walmart’, ‘Wal-mart stores’).

Continuing with this example, after all our strings pass through add_pair_to_lookup, we’d end up with:

>>> group_lookup

{

'Walmart': 'Walmart',

'Wal-mart stores': 'Walmart'

}

Vectorize the dictionary

We now map each merchant_name to a new grouped_merchant column in our final dataframe.

Finally, putting all the code together.

import re

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

from sparse_dot_topn import awesome_cossim_topn

#Import your data to a Pandas.DataFrame

df = pd.read_csv()

#Instaniate our lookup hash table

group_lookup = {}

#Write a function for cleaning strings and returning an array of ngrams

def ngrams_analyzer(string):

string = re.sub(r'[,-./]', r'', string)

ngrams = zip([string[i:] for i in range(5)])

return [''.join(ngram) for ngram in ngrams]

def find_group(row, col):

#If either the row or the col string have already been given

#a group, return that group. Otherwise return none

if row in group_lookup:

return group_lookup[row]

elif col in group_lookup:

return group_lookup[col]

else:

return None

def add_vals_to_lookup(group, row, col):

#Once we know the group name, set it as the value

#for both strings in the group_lookup

group_lookup[row] = group

group_lookup[col] = group

def add_pair_to_lookup(row, col):

#in this function we'll add both the row and the col to the lookup

group = find_group(row, col)

if group is not None:

#if we already know the group, make sure both row and col are in lookup

add_vals_to_lookup(group, row, col)

else:

#if we get here, we need to add a new group.

#The name is arbitrary, so just make it the row

add_vals_to_lookup(row, row, col)

#Construct your vectorizer for building the TF-IDF matrix

vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer(analyzer=ngrams_analyzer)

#Grab the column you'd like to group, filter out duplicate values

#and make sure the values are Unicode

vals = df['merchant_name'].unique().astype('U')

#Build the matrix!!!

tfidf_matrix = vectorizer.fit_transform(vals)

cosine_matrix = awesome_cossim_topn(tf_idf_matrix, tf_idf_matrix.transpose(), vals.size, 0.8)

#Build a coordinate matrix

coo_matrix = cosine_matrix.tocoo()

#for each row and column in coo_matrix

#if they're not the same string add them to the group lookup

for row, col in zip(coo_matrix.row, coo_matrix.col):

if row != col:

add_pair_to_lookup(vals[row], vals[col])

df['grouped_merchant'] = df['merchant_name'].map(group_lookup).fillna(df['merchant_name'])

df.to_csv('./grouped.csv')

Note: This blog was heavily inspired by Luke Allan Whyte’s work in which he built a python module named text-pack which does this task of grouping similar strings very efficiently and I would definitely recommend you all to have a look at it.

Thanks!!